History of Agriculture – Warra district

In the beginning…

For millennia the land in this area was tended by nomadic aboriginal people who depended on its natural produce for their food and fibre. Seasonal grasses provided these groups with a variety of grains. Vegetation produced nuts, fruits and berries. Animals, birds, fish and reptiles fed off these natural resources as well, extending the food supply for these nomadic groups. Continuation of these necessities for life and lifestyle was guaranteed by use of fire and an understanding of seasonal rotations and natural breeding habits.

It was after Alan Cunningham’s explorations of 1827, followed by Leichhardt’s trek through this area in 1844, that changes in the land management for the production of food steadily began to be noticed.

Southern graziers, in need of more land for their rapidly expanding flocks and herds, sent speculators north to the newly named Darling Downs. Henry Dennis was one of those young men. It was in the late 1840’s when he took up land along the newly named Condamine River for Clark Irving of Sydney. In time, Irving sold this land to Colin John Mackenzie. By the 1850’s, it was sold to Henry Thorn. Chinese shepherds and indentured German labourers capably tended flocks, constructed sheep folds, dug wells, established at least one vineyard and constructed irrigation systems for thriving well-tended market gardens. The area had been known as Cobble Cobble, the name of the aboriginal people living in this area. It had been called ‘Cooranga’ and ‘Cooranga North’, but Henry Thorn decided to call his land ‘Warra Warra’. It was on 3rd September 1877, when the Western Railway Line extension reached the small settlement that had become established here beside the Cooranga Creek, that Queensland Rail officially named the town and district ‘Warra’.

Pioneering Times …

The Warra district was slow to grow, and it wasn’t until about 10 years after the arrival of the railway and the Education Act in 1875 that extensive land selection began. Encouraged by the opening of the railway, Richard Best came to Warra in 1875 to build a bark shack that would become its first hotel, post office and store. In 1877 he applied to lease 291 acres of land in the Warra Homestead area.

Early 1900’s …

Until the turn of the century, grazing had been the principal industry, but the Federation Drought of 1902 ruined many and forced some to abandon or relinquish their holdings to be broken up for closer settlement. In the early 1900’s new lands were being opened up for selection, and the areas between Warra and Chinchilla were widely advertised, particularly to drought stricken Victorian farmers. In 1905 alone, there were 70 selections of land by Victorians and Germans in the district. The land selected was virgin brigalow and belah scrub.

Cultivating land to grow crops probably began around Warra when the rail first came through in 1877. Crops grown would have been corn, oats and sweet sorghum for feed for the draught and transport animals, and possibly some wheat as well. Initial cultivation would have been on the easily cleared open woodlands around Warra township. It is known there was a vineyard very early on, on Schroeder’s farm near the wheat silos at Warra, and a hand pump in the Condamine River on ‘Kalora’ where Chinese gardeners operated. There were also Chinese market gardens over the creek from the school near where some sisal cactus can be seen. This was most likely planted by Afghan camel drivers to allow them to make ropes at their campsites along the route before the railway.

With the advent of new country being opened up for settlement north and east of Warra in the brigalow scrub area in the early 1900’s, cropping took on a new intensity. Most of the blocks opened up were half square mile blocks (320 acres, or about 129 hectares) and dairying was the principal industry.

The dairy farmers used on-farm separators to separate the cream from the milk, and the resulting whey was then fed to pigs as a high protein supplement. The cream was brought in from the farm by horse and cart to be sent by rail to Toowoomba before the butter factories were built in Chinchilla, Jandowae and Dalby, and the pigs to abattoirs locally. Most of the butter and bacon produced from the cream was destined for export to Mother England. The cows were milked by hand, generally by the whole family, and crops like corn were planted by hand with walking stick planters.

Corn was a favourite crop because the cobs could be readily hand harvested and it could stand in the field for some time. It was an excellent source of sustenance for the draught animals and could be planted through spring and summer.

Crops were cut by hand or with a horse drawn reaper and binder. The loose hay or stooks made by hand, or sheaves made by machine, were then transported to make haystacks for feeding the stock and draught animals throughout the winter months when there was little feed available.

Storing grain was a difficult process. Keeping mice and weevils out was greatly problematic without the chemical pesticides we take for granted today. Indeed, even today, in many parts of the world 25 percent of the crop is lost to pests. Some farmers kept their feed and seed grain in galvanized storage tanks with the inlet and outlet sealed with bees wax. Before sealing the lid, they lit a candle in the void above the grain, and the resulting burn exhausted all the oxygen in the air inside the tank keeping it weevil and mouse free. Although this is not practical or cost effective on a large scale, it is still effective on a small scale today.

The widespread adoption of tractors from the 1920’s transformed the area and the shift from livestock to cropping began in earnest. What is little understood is that every farm needed to set aside around 25 percent of its area just to grow grain and fodder for its draught animals, and farmers could easily spend 25 percent of their time maintaining the draught animals and their harness. Catching the horses at 4am, grooming, feeding, checking shoes and hooves, and then the regular rest periods that the horses required all day long may nowadays sound romantic, but the cost, drudgery and fatigue of it every day is evidenced by the swift change to tractors. Farmers could now produce 33 percent more product on the same area, and do it with much less physical labour. Worldwide, this led to a massive increase in agricultural production, and is credited with creating the great American dustbowl of the 1930’s. Some say it was also instrumental in creating the great depression. Although the depression was devastating for many rural areas, there is not a lot of evidence that the Warra district was as profoundly impacted. This may be because butter and bacon and wheat which was by then being grown were staples. Additionally, this was at the height of the prickly pear invasion which possibly overshadowed the impact of the depression

More modern tillage and planting machinery, and drawn harvesters also became the norm throughout the 1920’s and 30’s, increasing productivity very significantly. However, clearing the land of the thick brigalow, belah and tea tree timber was still a slow and tedious process. First the thick scrub had to be ringbarked, and then when dry it was burnt and all the sticks picked up by hand.

Leasehold Tenure …

The blocks were leasehold tenure issued by the Government and the provisions were that the lessee had to clear and fence the land at a certain rate or the lease was forfeited back to the crown. Many found this too much and walked off.

Prickly Pear …

In the 1920’s the prickly pear invasion arrived. It completely enveloped the land and the scrub where it was not controlled, and control was very difficult without herbicides. Any leaf that broke off and was not picked up regrew as a plant very quickly, and if a bush was knocked over, every leaf grew as a plant. Emus ate the fruit and spread the seed far and wide in their droppings. A bounty was declared on them to try to stop the spread, and other birds also contributed.

The prickly pear, which was first grown as an ornamental garden cactus at Scone in 1838, eventually spread until it engulfed fifty million acres by 1920. With its seed carried by birds, livestock and floods, the plant thrived in the Warra-Chinchilla area to such an extent that the region was considered one of the worst areas of infestations.

With many settlers walking off, the Queensland Government introduced the cactoblastis caterpillar from South America to control the pest, and it has been one of the world’s most successful biocontrol programs. The Warra-Chinchilla region was chosen as the site for the cactoblastis experiment that was a phenomenal success. The cactoblastis ‘egg sticks’ were gathered and 2 shillings and sixpence an ounce (approx. 25 cents per few grams) was paid for the eggs to be spread onto new patches of pear. Some of these eggs were sent to New South Wales to counteract the prickly-pear infestations there. Within a couple of years most of the pear was gone and farming began again in earnest.

During the War years …

In both world wars, many local farmers and their sons and daughters enlisted which left a great void in the workforce. Old men, wives and children all stepped up to the plate and kept the farms running and productive. Fuel was rationed and input supplies were scarce. Many farmers ran their vehicles and some tractors on charcoal burners which used a fire to heat charcoal to make gas to run the engine. It was a very slow and costly way but sometimes the only way to town or market.

After WWII, surplus army dozers and tanks became available which aided in quickly clearing the land. Larger more modern machinery allowed more land to be planted and harvested much quicker than just a couple of decades earlier, and many farms swung out of dairying into wheat, beef cattle and sheep. Dingoes were a constant problem for sheep which constrained their production.

Warra at the time had two major sets of cattle saleyards (the remains of one can be seen on the north side of town) and one set of sheep saleyards with regular sales. But the advent of better roads and larger trucks meant these sales gravitated to the larger centres.

Also after WW11, some large properties north of Warra were resumed and broken up and balloted for soldier settler blocks. This brought many new families to the area as the properties resumed had been large leasehold tenures. The soldier settlers were a colourful lot and some of their descendants still farm in the area. But with no prior experience in farming for many of them, quite a few struggled to make a profitable living. The Trumpeters Corner story is a testament to the high spirited soldier settlers.

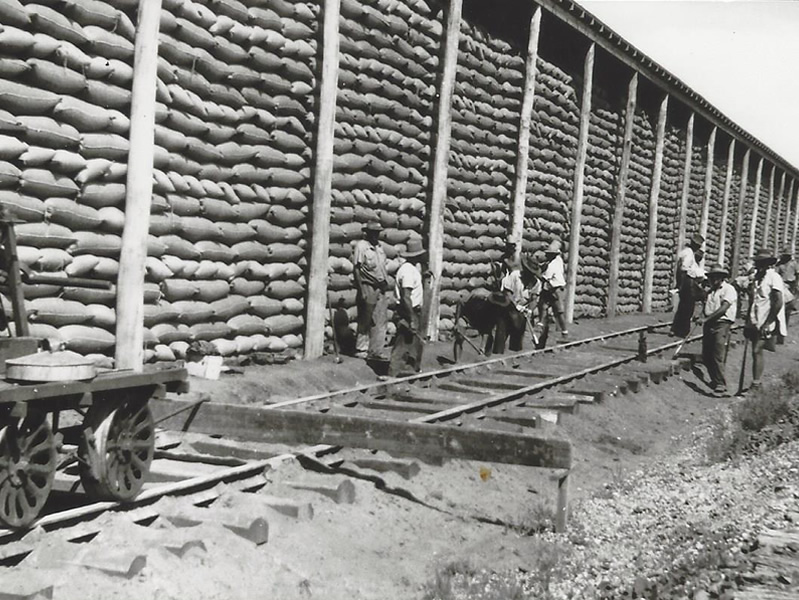

The Warra Bag Shed …

The 1947 wheat harvest looked promising and bulk storage was needed before harvest. The State Wheat Board was in the process of constructing large, covered bag sheds. In September 1947, at the site of the proposed Warra Bag shed the Francis brothers, using their own tractor, began boring the holes for the 96 bag shed poles. The plan was for the bag shed to have 19 bays. Timber was sourced from nearby Kogan. Local farmers using their own trucks transported the timber to the site. Construction began in earnest.

The weighbridge was constructed of poles and sheets of galvanized iron. It took 2 local men all night to hand dig the 40ft x 9ft trench for the weighbridge scales in readiness for the Bag shed to become operational for the intake of the harvest. The bags of grain were lumped manually and the shed soon filled with its first harvest intake.

Grain Production …

Bulk grain replaced the bags very quickly around 1960, and the bagging shed and teams of workers to sew, load and stack the bags became a thing of the past overnight. Harvesters became self-propelled, and tractors doubled in horsepower. Grain production in the area boomed.

These were prosperous times for Warra, and the town boasted a New Zealand Loan Stock and Station Agency, a machinery dealer selling tractors and ploughs, a bakery, store, café, butcher and two garages. The Warra State School had over 100 students, and there were many one teacher schools scattered throughout the area. In 2021, the school has less than 20 students, and all the one teacher schools have long gone. The massive increase in productivity on the farms, whilst necessary to stay profitable, has meant a great depopulating of the area, as has happened worldwide in farming areas.

In the late 1960’s, wheat production worldwide was excessive and the price plummeted. By now, the Australian Wheat Board controlled all wheat marketing in Australia by government statute, and to limit production, quotas were introduced on production. This created a great deal of difficulty for many farmers, and alternatives to wheat were quickly sought. Sorghum, barley, sunflowers and millets were grown extensively in the area, and sorghum and barley have remained as staple crops of growers till this day. One major pest of sorghum is the sorghum midge which can completely annihilate flowering crop and required pesticide applications to save the crops. In the 1990’s Queensland scientists bred midge resistant sorghum and now the crop is only sprayed very occasionally for midge. The midge resistant sorghum was a world first, and has benefitted the area greatly.

Legume Crops …

Through the 1970’s, it was recognized that growers needed alternative crops and legumes such as mung beans and chick peas were introduced. These legumes are still significant crops around Warra.

Cotton Farming …

Then in the 1980’s, reacting to another worldwide crash in grain prices, many local farmers began growing dryland cotton very successfully. This rain-grown cotton was much more profitable than the grain crops and gave the whole district a significant boost, but the cotton growers still rotated with grain crops.

Cotton crops required extensive protection from pests, and local growers were at the forefront of industry research to reduce pesticide applications. In 1996, the first genetically modified (GM) crops ever commercially planted in the world were GM cotton crops planted across Australia. In the 25 years since, farmers have gone from regularly spraying their cotton crops often to not spraying them at all, and from teams of chippers in the fields to clean the fields without the need for cotton chippers. The cotton is now harvested by large machines that wrap the cotton in plastic as it is picked. Previously cotton was carted off the field in buggies and compressed into modules by teams of workers. While all these innovations have meant remarkable improvements in efficiency and the environment, the downside is that there are less people required to do the work, with the resulting lower population locally. In the 1990’s, one local farmer began breeding and growing naturally coloured cotton and was one of the first in the world to do this. At one stage Warra grew more coloured cotton than anywhere else in the world. Although the project was successful, the inability to produce more colours than brown and green, and some international factors, led to the phasing out of the industry.

GPS Technology …

The advent of GPS technology in the late 1990’s allowed farmers to enter the world of self-steering tractors, harvesters and sprayers. With satellite signals up to 50 times a second, these giant machines stay on course +/- 20mm. Growers quickly adopted this technology, and used it to institute a system of ‘tramlining’ where the machine wheels stay on a predetermined path (tramline) for each pass of the field. This means there is no compaction anywhere else in the field, and farmers are seeing massive increase in water infiltration and retention due to this process. Productive crops need only water, nutrients and sunlight to grow, and if water is limited because the soil has not held enough, unprofitable crops will ensue.

Farming Systems …

Hand in hand with this massive advancement, came zero till. This is a system where farmers use herbicides to control the weeds and leave the stubble standing in the fields. This creates a blanket on the field and stops evaporation, and stops the root holes and worm holes being sealed off by cultivation allowing much better and more rainfall infiltration and retention. Initially, there was some debate over this system, mainly because it was not ‘natural’. But nature does not plough. The grass on the plains and prairies, and the trees in the forest all stay in place once they die until the next generation replaces them. This is exactly what we are recreating in our modern farming systems.

Modern Farming Facts …

The silos that you see along the highway are not used as much today as they were in the past.

Many farmers have their own storage systems.

This allows the farmer:

- To harvest a crop quickly if bad weather is coming

- To hold grain and sell when prices are more profitable

- Save on time if there is line up at the dump when a truck is needed in the paddock. Also when the dump is not operating on the weekends and a crop needs to come off.

The soils in the Warra district are generally a grey cracking clay with high moisture holding ability. The cracks allow the rain to penetrate deep into the soil.

Farmers often use a weed seeking technology to only spray the weeds and not the whole field. Put simply – this is a spraying bar that has many little cameras and has the technology to pick up the difference in colours between a plant and stubble.

Implementing new precision agriculture technology is a smart move for Australian farmers, but it is a major investment. The benefits are:

- Allow farmers obtain large sets of data

- Improves understanding of paddocks and plants

- Adds a level of accuracy to certain operations

- Increase yield

- Reduce wastage

- Save time

- Cuts costs

Most farmers have their own agronomists…

Agronomists are scientists, whose area of study is plants and soil, in order to increase productivity, develop better cultivation, planting and harvesting techniques; improve crop yield, quality of seed and nutritional values of crops; and solve problems of the agricultural industry.

Feed Sorghum …

Around 2010, world and local demand for feed grains (sorghum in particular) and chick peas skyrocketed, with the value of these crops overtaking cotton in value to the producers.

South East Queensland is the feedlot capital of Australia, and there are several hundred thousand cattle on feed within a 100klm radius of Warra at any one time creating a wonderful opportunity for local farmers to supply this industry with sorghum, corn, barley and wheat. Around the same time the world ran short of chick peas and the prices escalated which resulted in many more being grown, despite challenges with disease and insects.

In about 2015, China began buying our sorghum as a premium feedstock for their baijiu (liquor) and the price rose significantly, but as at 2021 this market is subdued with trade bans by China on sorghum. However, some sorghum is still finding its way to China.

The egg industry also relies on sorghum to give eggs their nice yellow yolk. Many other countries allow artificial feed additives to create this yellow yolk, but with our sorghum we do not need this.

Heliothis …

It is interesting to note that heliothis is the major pest of agricultural crops in Australia, particularly sorghum, corn, cotton and chick peas. These insects are now controlled in sorghum, corn and chick peas with a biological insecticide which has no deleterious impact on any other organism, and is naturally occurring. The commercial production of this insecticide requires the production of millions of live caterpillars per day in controlled environments to make the insecticide which is a nuclearpolyhedrosis virus (NPV). Heliothis in cotton are remarkably controlled by the natural Bt insect toxin produced by the plant with genetic engineering. As with the NPV, the GM crops have no deleterious impact on the environment or human health.

Australian production of NPV’s (VIVUS) started on a farm north of Warra in 2001 and the company now has a factory in the United States and sells NPV’s for a range of insects all over the world.

Changes in Agriculture …

Warra’s agricultural practices have evolved through many phases: broadscale sheep, intensive small scale dairy, cattle, and now broadacre automated farming enterprises. As in all industries, efficiency and scale are the key to production and profitability, and Warra’s farmers have been forced to scale up and automate with the unfortunate result of local population decline. In recent years, corporate farms owned by Australian and international superannuation and pension funds have purchased large tracts north and east of Warra further exacerbating this decline.

Agricultural fortunes worldwide fluctuate wildly with droughts, floods, oversupply and shortages, and now international trade wars.

Warra’s farmers have remained resilient and adaptive through all these challenges, and currently can boast some of the best farmers in Australia. Whilst many farming communities struggle with elderly farmers and children leaving the area never to return, Warra is blessed to have a whole generation of younger farmers taking up the reins, and leading us into the next exciting decades.

Contributed by Jeff Bidstrup, “Prospect” Warra

Explore Warra Queensland, and Discover One of Australia’s Hidden Treasures